Nick Offerman is not an overswirler. Image Source: Lagavulin, YouTube.

Every evening in five thousand fine restaurants across the country, it happens again, this involuntary ritual, this collective tic. A server stops, sets a drink on a table or bar and walks away. A hand extends, grips the glass, and swirls. And swirls again. There is variety in the technique, to be sure. Over there sits the violent agitator, bravely testing the tensile strength of a thin stem of Austrian crystal. In the corner we have the studious, steady swirl of a man alone who chuckles as he sends away the small carafe of supplemental water for his neat pour of something alarmingly close to cask strength. By the bar, it's the nervous jerking swirl of the man whose Tinder date is concerningly late, but who learned in college that a drink manipulated from time to time can transform an awkward weirdo standing around looking creepy into just some dude.

It would be one thing if it were just wine.

But it isn't just wine. Good people, we are out there very earnestly swirling old fashioneds and cosmos and margaritas and manhattans and martinis. Martinis! This is a drink which, in the modern vernacular, basically amounts to ethanol and distilled water served very cold in a glass of a particular shape.

We are a nation of overswirlers.

It isn't that there isn't reason to swirl. Sometimes. A lot of the esters, aldehydes and sulfuric compounds like thiols that influence the aroma and flavor of wine are volatile and have a pretty high vapor pressure, which means that they are more likely than many of the other substances comprising a liquid (e.g. water) to evaporate and get in your nose. But they're not that volatile, which means that spurring some additional evaporation can accelerate getting more of those volatile aromatic compounds out and about.

Sometimes we swirl to smell.

And sometimes we swirl not to smell.

The human's main path to not smelling something is called olfactory habituation, more commonly known as noseblindness. It or similar habituation mechanisms exist across a range of sensory processes in humans and other animals. Olfactory habituation describes how our brain reduces the importance of static stimuli and increases the importance of new ones. From an evolutionary perspective one understands the appeal. If our sense of smell were only related to the quantity of odorants capable of interacting with neurons at any given time, for example, early man would have smelled his unbathed, sweaty self at all times. That would leave the fainter - but novel - scents of other humans, prey, animals and dangerous conditions unregistered. Not great, Bob.

There are two principal analogs to unwashed hunter-gatherer pits when it comes to well-made wine: ethanol and sulfur dioxide. The former is what makes booze boozy, of course, while the latter is added by many winemakers to arrest fermentation, prevent oxidation and otherwise keep wine from going bad. Sulfur dioxide has such a ridiculously high vapor pressure that it takes significant effort to avoid it gassing up a whole room. Best case, it's halfway across the room by the time you've started pouring, probably too faint to give anyone even the notion of bad eggs, but maybe enough to make them think about that gross hot spring scene in Dante's Peak. Worst case, it's a swirl and a sniff and it's gone. Ethanol is not so volatile. By swirling the glass a bit, the burning sensation of ethanol in wine that you'd probably be done with half-way through your first glass you can instead induce noseblindness to before your first sip. After that, your brain is free to identify all sorts of interesting (good and bad) flavors and aromas that made it into the wine.

For most mixed drinks, we can easily shortcut what swirling would tell us: that "aroma" is a sea of cranberry juice, lemon juice, lime juice or simple syrup.

For most neat spirits or effectively neat derivative cocktails, ethanol accounts for 40-60% of the liquid. The nature of the distillation process that made that spirit is to prioritize getting stuff with a high vapor pressure into the next vessel instead of stuff like water with a low vapor pressure. To be fair, there are cuts in most distillation processes that seek to eliminate the very, very first stuff to boil off, including methanol (an alcohol that makes you dead after a single standard shot at 80-proof). By and large, however, the nature of a distillate is to contain a lot more of the stuff that is going to be assaulting your senses as soon as you put it in your glass. Put simply, you do not need any help going noseblind to a 45% ABV spirit. Three fair sniffs and your brain has sampled enough air saturated with ethanol vapor to say "I got it, I got it, you're high proof. Enough already."

If you're doing a critical whisky tasting of an original bottling of one of the last years of Port Ellen or a '66 bottling of Springbank Local Barley in a controlled environment, of course, and really want to see what other aromas may be hiding below the surface at various points in the tasting, then swirl away. Add water. Change the temperature of what's in the glass to affect what's staying in the liquid and what's coming out. If you're betting on being able to get anything out of that in a bar across from a kitchen broiling tomahawk ribeyes and poaching lobsters, I think it's a lost cause, but you do you.

In any case, it's all chemistry.

It's also a bit of a dance.

It's a dance between inducing noseblindness to the thing we don't need reminders of on the one hand, while also preventing it from spoiling our enjoyment of all the aromas we do want on the other. It is a bigger question for us, I think, as consumers of far more than smells:

How do we retain a functional filter on noise while also keeping ourselves from going noseblind to ongoing things that still matter and warrant our engagement well after some discrete event?

Our first real sniff of the baby formula crisis in America was on February 17, 2022.

That's when the FDA announced that inspections of an Abbott Labs facility in Sturgis, Michigan had uncovered evidence of cronobacter contamination in some Similac, Alimentum and EliCare powdered baby formula products. Within two weeks, the FDA and Abbott announced several hospitalizations and two deaths in connection with the contamination.

While the news included discussion of both a recall and shut-down of production at the facility, the principal framing of this news event was the contamination itself, along with the injuries and deaths it caused. There was some discussion of potential shortages, but frankly, not very much. Next-day coverage of the deaths published on March 1 represented the peak in coverage among US outlets. It took 33 days for the coverage volume to fall to half of that level. It took only 5 more days for coverage to fall to a just quarter of March levels, which it did on April 8, 2022.

Outside of media world, it was common knowledge among parents of young children and anyone who knew them that baby formula was already in massively short supply during this period. I should know. I had a 10-month old daughter who out of necessity received probably 50% of her nutrition at that stage from Enfamil powdered formula. I had ordered a three-month supply after reading the limited Abbott news in February. Every time I went to the grocery store or pharmacy, and every time I placed an online order of any kind between March 1 and May 11, 2022, I looked for and tried to buy the Enfamil our daughter needed. No luck.

In the meantime, the media and the general public had gone noseblind to widespread issues with baby formula, even though the underlying news event was different. It was no longer just about a single contamination event and the tragic losses it caused for a few families. It was about the utter unavailability of a critical product with practically no substitutes for millions of families for whom breastfeeding could not provide adequate nutrition. But almost nobody was writing or talking about it.

It wasn't until May 9 and May 10 that we got our second whiff of the baby formula crisis. That's when the New York Times published its long-form feature, "A Baby Formula Shortage Leaves Desperate Parents Searching for Food." Other outlets followed suit. The reframing toward "shortage" coverage accelerated when the Biden Administration announced two initiatives on May 18th: to invoke the Defense Production Act (DPA) and to fly in certain foreign-manufactured formulas that met FDA standards, a program dubbed, uh, Operation Fly Formula.

When your orchestrated photo op inadvertently shows exactly how miniscule and superficial a government rescue program was. Source: UPS

Coverage continued and reached a peak within a week, on May 26.

And then it declined. This time it took 14 days for coverage to fall to half of that peak level. It took 19 days more to fall to a quarter. By this time in June, much of the coverage was of how preposterously limited the supply unlocked by Operation Fly Formula was, as in this rather Fiat News-tilted June article from the Washington Times. As to DPA coverage, it was practically non-existent, as journalists seemingly had trouble finding evidence that the authority was being used on anything material. And no, government authorization to let Cargill fill orders for corn-based sweeteners to Reckitt and Abbott ahead of some other commercial clients does not qualify.

And so it fell even more. By July 24th, coverage was about an eighth of its peak. By August 26th, it fell below 5%. By the holiday season, media coverage of the massive baby formula shortage was less than 2% of volumes when administration officials were giving pressers and big companies like UPS were updating their About Us pages on their corporate website to show their planes in the background of a single pallet of Nestle baby formula.

Our family was fortunate that little Eleanor was already a year old. By mid-summer, we gave up on trying to find those rarest fruits of the administration's hard work fast-tracking corn syrup solid orders and flying over a couple cans of formula from Switzerland. We transitioned her to solids about 6 months earlier than we would have otherwise, but she took to it well.

We know a lot of families who weren't so lucky, who drove hundreds of miles in desperation more than once, who were glued to "moms lists" on Facebook so that they wouldn't miss the 15-minute window to race to Walmart once another mom reported that they had seen three cans in stock. We talked with families about the substitutions they were forced to make, knowing that they were not giving their infant adequate nutrition. We know churches who tried to coordinate breast milk networks and banks and homeschool co-ops that did the same. Moms who were already shamed constantly about not being able to breast feed as much as they desperately wanted to were now having a whole new layer of guilt heaped on them.

But collectively? If you weren't squarely in the cross-fire of this shortage, by early August you were probably noseblind to it. I don't mean noseblind to the coverage of the media. I mean noseblind to the underlying, still-very-much-a-thing issue that the coverage (or lack thereof) was about. After all, how the media covers an issue both influences and reflects how we as humans are all processing and thinking about it.

To be fair, it's not as if every story can be covered forever. Or should be, for that matter. It's a dance, you'll recall, filtering out the noise without killing the plaintive signal of a continuous news event.

As much as I would love for the cover story on the NY Post every day to be "The Astros still swept the Yankees in the ALCS", it is, alas, a singular news event. Its continuation as a state of the world is not newsworthy. The months-long continuation of a massive shortage of a critical household food commodity, however, is newsworthy even in the absence of an discrete novel event. The absence of meaningful use of DPA in a crisis of this magnitude was newsworthy, even in the absence of a discrete novel event. The steadfast resistance of the FDA to consider streamlining and fast-tracking formulations and ingredients considered safe across the developed world was newsworthy, even in the absence of a discrete novel event.

In both cases, it is useful for the citizen and consumer of news to understand the typical duration of the news cycle, as well as the kinds of things which might affect just how quickly we go noseblind to both discrete and continuous news events.

To that end, we decided to explore the media cycle for more than just the year-long baby formula crisis. The politically diverse Epsilon Theory team identified 25 different major news stories from the last 5 years or so. Five of the stories were discrete news events, or events we think most people would agree were relevant at the time they occurred, but which otherwise had very little in the way of ongoing newsworthiness.

- The Houston Astros winning the World Series in 2017

- The death of Queen Elizabeth

- The burning down of the Notre Dame Cathedral

- The blocking of the Suez Canal by the Ever Given

- The confirmation of of Ketanji Brown Jackson

Twenty of the stories were continuous news events, or events we think a large group of people would consider to have implications and sociopolitical relevance that extended well beyond the initial event. Sometimes that continuation might mean continuation of real-world effects. Sometimes it might mean ongoing social debate. Sometimes it might mean obvious but important unresolved questions left unresolved. Because our list includes some events important to divergent tribal narratives in the United States, you are unlikely to agree that all of these remained newsworthy. Or you might think they were continuously newsworthy for almost polar opposite reasons from someone else (think Hillary emails or Hunter Biden's laptop). You will, I think, agree that at least many of the twenty items below remained newsworthy well after some proximate trigger of media coverage.

- The baby formula shortage of 2021-2023

- The Afghanistan withdrawal

- The antibiotic shortage

- The Cambridge Analytica revelations

- Claims of emolument clause violations

- The Dobbs ruling (i.e. overturning of Roe v. Wade)

- The Defund the Police movement

- Jeffrey Epstein "committing suicide"

- 2014 spikes in border crossings

- 2019 spike in border crossings

- Hillary email server claims

- Hunter Biden laptop claims

- Keystone XL cancelation

- Las Vegas mass shooting

- The Panama Papers

- The grounding of the 737 MAX

- January 6th aftermath

- January 6th hearings

- Benghazi aftermath

- Benghazi hearings

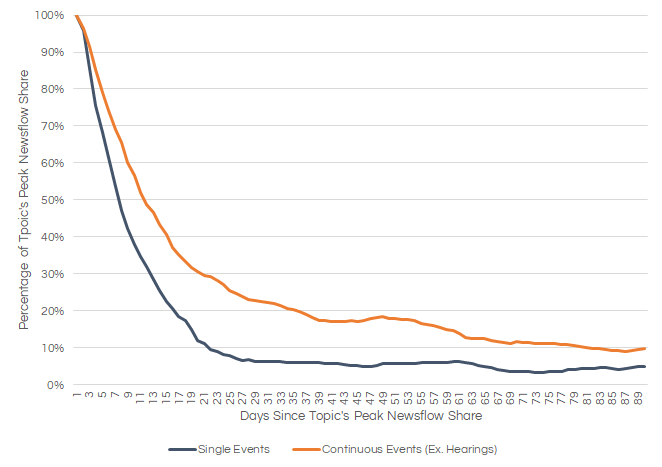

We measured the number of articles in our aggregate news dataset with language indicating references to each of these events on a daily basis. We then calculated the share of aggregate news flow represented by these articles over rolling 2-week periods and plotted the trajectory of that share of newsflow over the ensuing 90-day period relative to that peak.

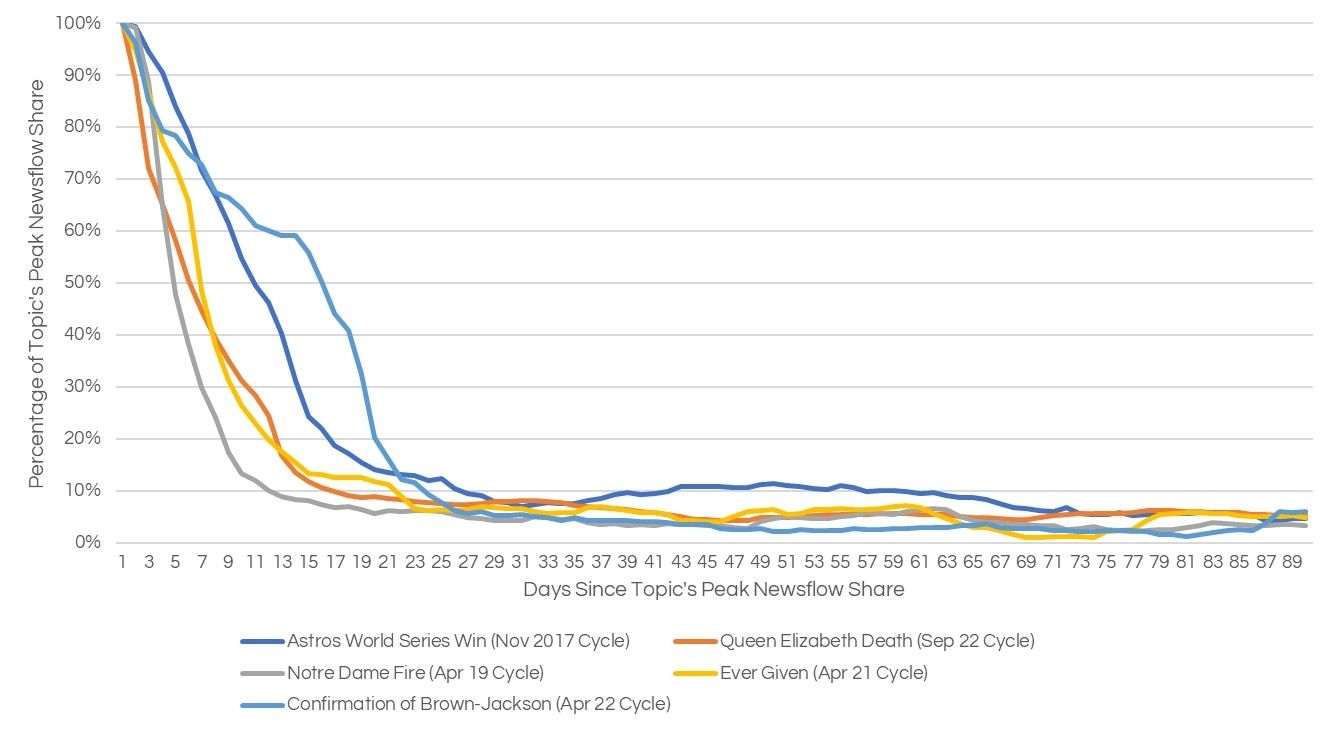

Let us first take a look at the news cycle of our collection of discrete news events.

Share of Aggregate News Flow by Days Since Peak Coverage - Selected Discrete News Events

Source: Lexis Nexis, Factiva, Epsilon Theory

There is some deviation in noseblindness among topics. The confirmation of Justice Brown Jackson, for example, was an event that took place over several days. We still consider it discrete because it had an identifiable beginning and ending. Sports media is also a different beast. For most professional leagues, the season ends with a championship, after which there is less to talk about. It should not be surprising that there is a longer tail for the last relevant topic. We still think there is a clear representative underlying pattern: the half-life of a discrete news event is about one week. One week.

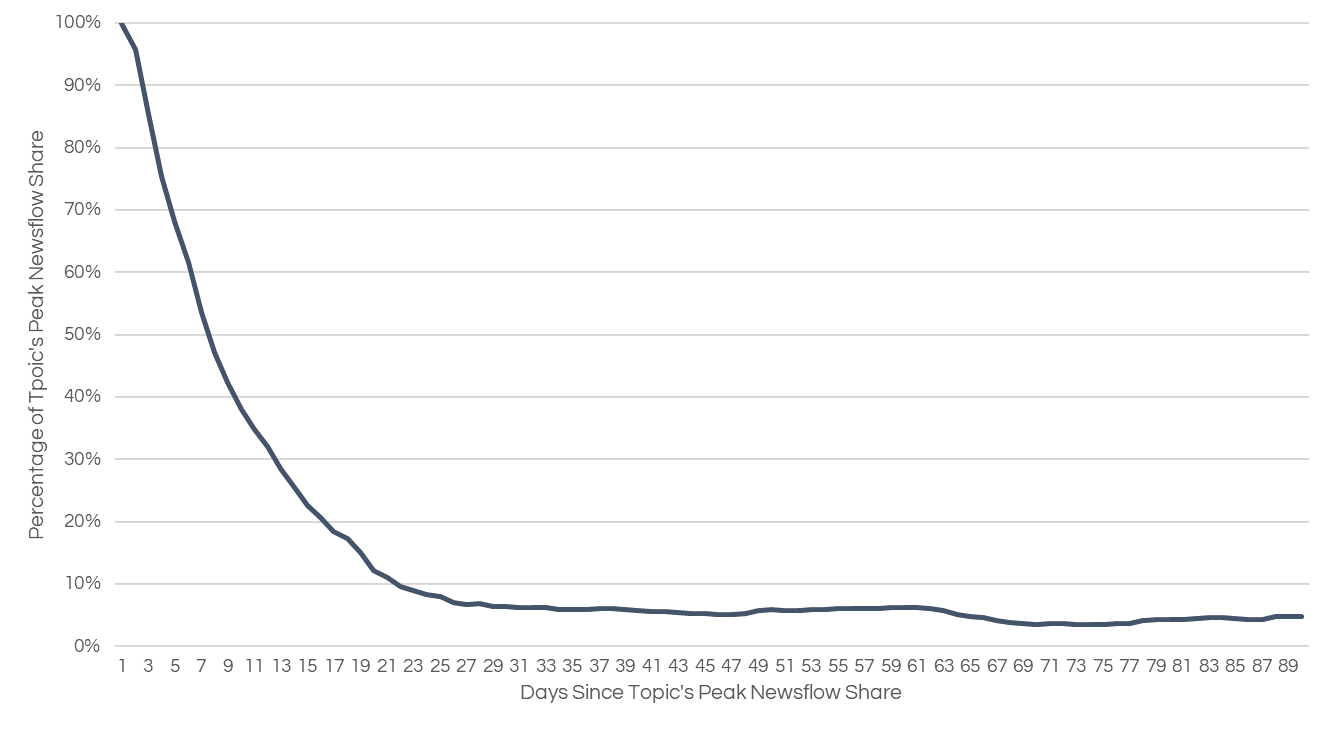

It takes us about five weeks to go completely noseblind to news.

Share of Aggregate News Flow by Days Since Peak Coverage - Aggregate of Discrete News Events

Source: Lexis Nexis, Factiva, Epsilon Theory

But what about those events of (subjectively) continuous newsworthiness? Surely they stick around much longer.

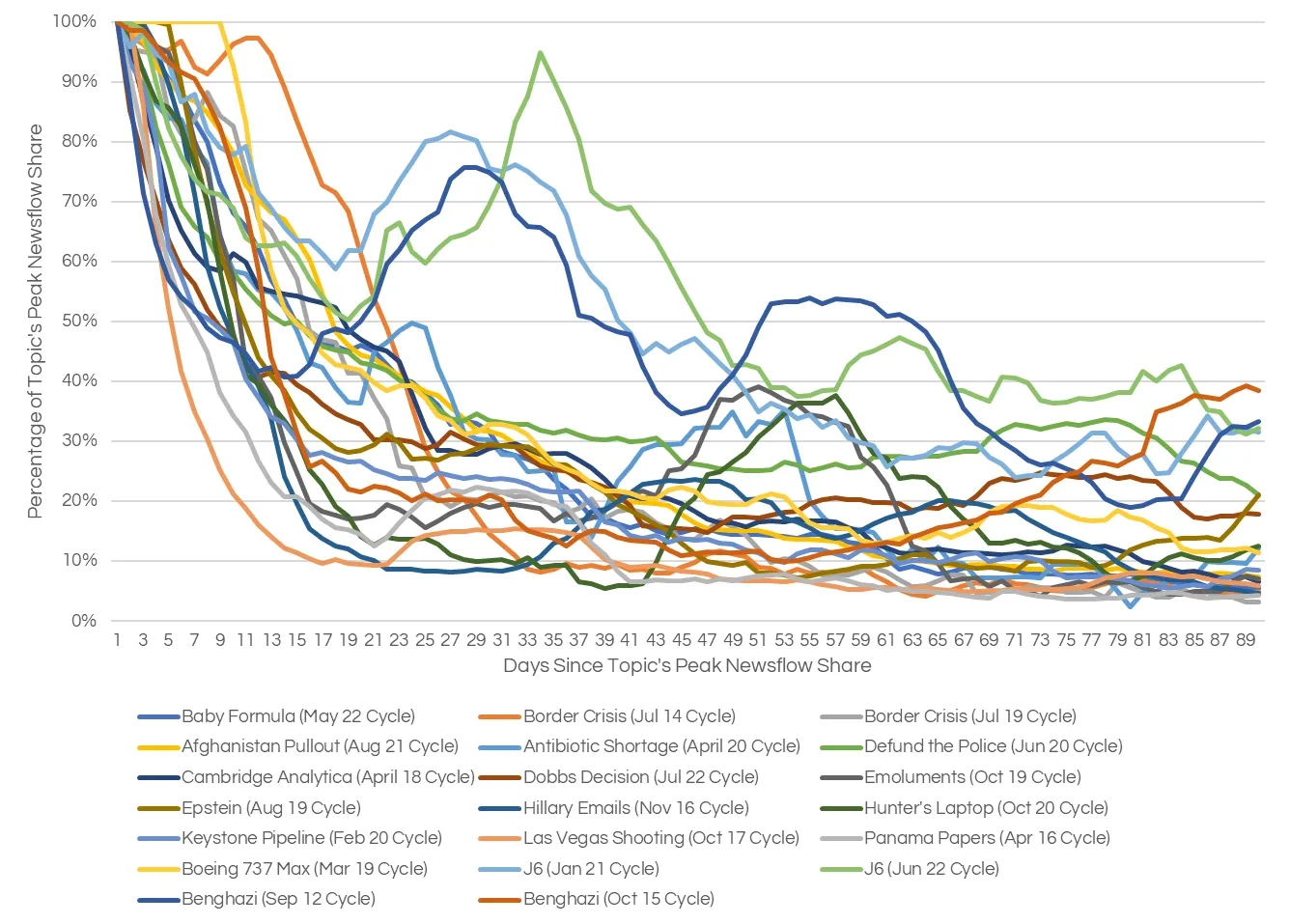

Share of Aggregate News Flow by Days Since Peak Coverage - Selected Continuous News Events

Source: Lexis Nexis, Factiva, Epsilon Theory

Or not. Like the discrete news events, coverage of continuous news events also declines rapidly. Still, it is certainly more of a mixed bag. Some even manage to bounce back into the public consciousness a few weeks along; however, four of these continuous news items represent coverage of political hearings or threatened hearings. These are topics with daily discrete events, whether they be speeches from notable politicians working to keep them in the news, or literal hearings covered and summarized by every major outlet. Cut out the J6 and Benghazi events, and the picture starts to look a lot more familiar.

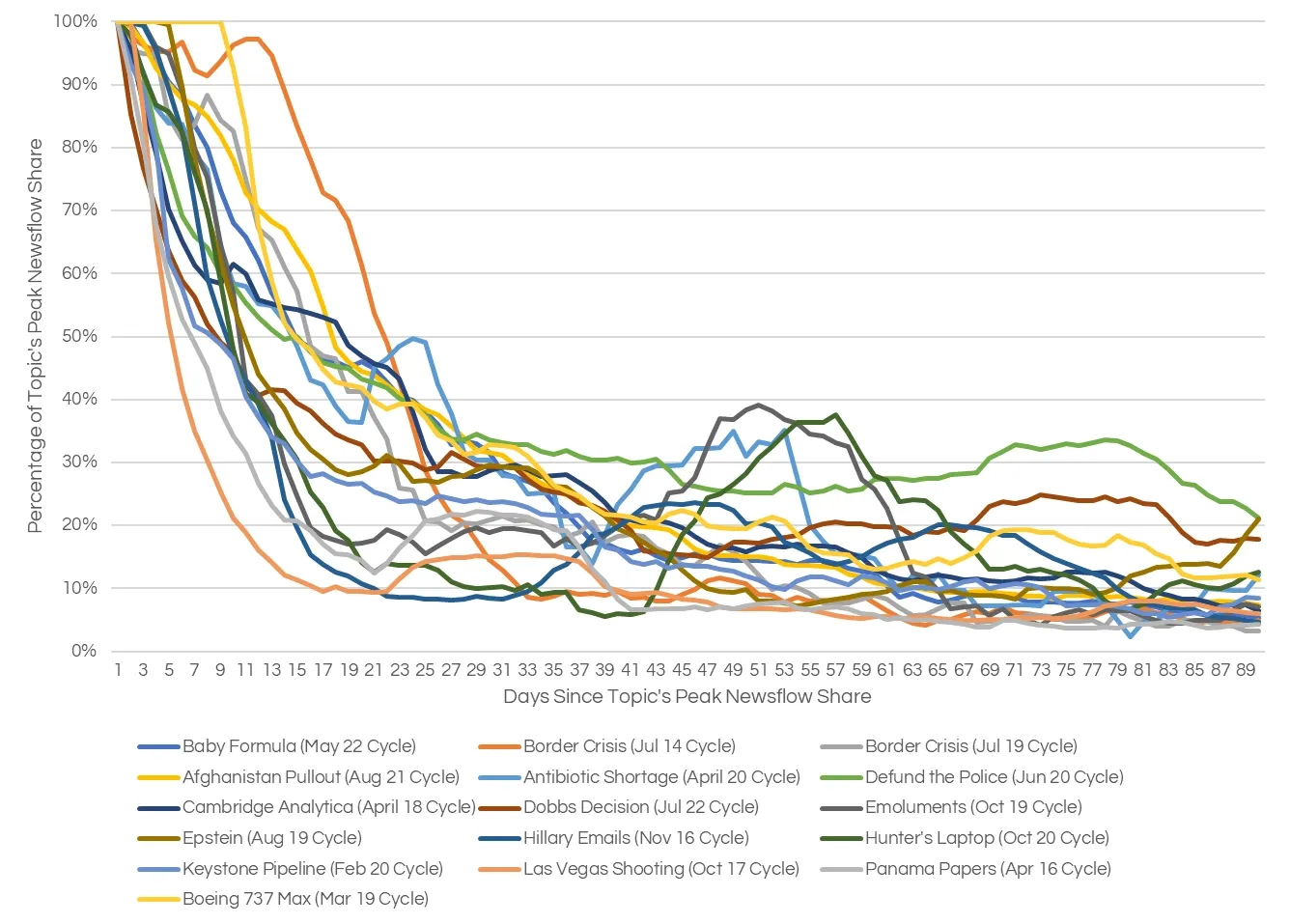

Share of Aggregate News Flow by Days Since Peak Coverage - Selected Continuous News Events (Ex-J6/Benghazi)

Source: Lexis Nexis, Factiva, Epsilon Theory

At least relative to the two-week half-life of discrete news events, some continuous news stories made a good showing. Coverage of Defund the Police and BLM rallies (or riots, depending on your predisposition) gave it a good go. The Dobbs decision hung in there for a while, I suppose. A few enjoyed a "new" cycle about 7 or 8 weeks in after a new discrete event, before immediately adopting the regular two-week decay cycle of everything else.

But by and large, there isn't a major difference in the typical rate of decay coverage of still-newsworthy items with ongoing relevance and that of discrete news.

Remember the Panama Papers? We went noseblind to them faster than for the average discrete news event. Remember the border crisis in the summer of 2019? Remember the politicians who visited and witnessed the conditions? Among all topics, both discrete and continuous alike, we only went noseblind to the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral more quickly than the 2019 border crisis. Practically zero answers, zero cameras and zero reasonable explanations later, our brains and our media moved on from the 450+ wounded and dead concertgoers in Las Vegas. Even the, ahem, suicide of Jeffrey Epstein, with all of the unanswered questions about his death, the case, and the consequences for others implicated, was a hair's breadth away from the decay rate of your run of the mill story about the winner of a sports championship two months prior.

Share of Aggregate News Flow by Days Since Peak Coverage - Aggregate of Discrete and Continuous News Events

Source: Lexis Nexis, Factiva, Epsilon Theory

Barring new discrete related events, complete noseblindness at the broadest level of American society should be expected within two months of just about anything that happens in the world.

I don't think there's much we can do about this from the top down.

While this is a media problem, I think it is a human brain problem first. The idea that there is some way to structure our media to continuously bring attention to the Panama Papers, or Epstein, or how the Afghanistan pullout went down, or an epic shortage in food and medicine for babies without additional discrete events in ways that amount to more than "Yep, this is still happening and it still sucks" is hopelessly naïve. It is hard enough to keep a hard news outlet from going belly-up as it is. Writing stories people won't read - again, it's a human brain problem first - isn't going to help.

I still think there's a lot we can do about this from the bottom up.

Back before it had become yet another useless word caught up in the gravity of the widening gyre, being "woke" was once just the idea that there were lingering effects of racial and other biases to which society had gone noseblind - and that it was worth making a conscious effort to look at the things our senses told us to ignore.

No matter how skeptical we might be of that underlying claim, no matter how dismissive we might be that the social and policy implications are self-evident, there can be no doubt that we humans routinely go noseblind to events and issues with ongoing consequences.

There can be no doubt that the answer is a community of individual citizens who constantly remind one another to be vigilant, to remain awake to topics we consciously determine remain worthy of our attention even when our senses are calling them noise.

And there can be no doubt that our commercial media will never - can never - be that watchman on the walls.

So what can we do about it?

We can consciously track our media consumption.

We can develop ways to check when we have been bombarding our senses with certain topics.

We can develop ways to check when topics have fallen off our news consumption radar.

We can connect with a community of others trying to do the same - and to hold one another accountable for remembering.

In short, we can create a new woke movement.

No, not a movement of performative public expressions designed to pay obesiance to The New Thing in exchange for social credit and indulgences. A movement to remember. A movement to fight our human tendency toward noseblindness when it makes citizens forget what is still important.

We have been talking about our Narrative Early Warning System, or NEWS, initiative here at Epsilon Theory for just about a year now. Ben introduced it in an March 2022 essay called The Luther Protocol. Shortly thereafter, we announced a small role in a partnership with the McGee Family and Vanderbilt University to establish the McGee Applied Research Center for Narrative Studies.

The goal of NEWS is simple. We want to make it possible for citizens to make up their own minds about what's happening in their world.

One important part of that mission is raising the citizen's awareness of when media and other influential institutions and individuals are telling us how to think about the news. Tentatively scheduled for release in the second quarter of 2023, our Fiat News subsite will track aggregate levels of opinion-injecting language across news outlets and topics over time.

As Ben has pointed out in The Luther Protocol, we are also working to develop user applications that have two core features. One of those features is to provide a real-time view of the hotspots of opinion-injecting language within any content being consumed, using Epsilon Theory's fiat news language models. The second is, for users opting in, to provide over-time feedback about their own news consumption habits. Some of that feedback will concern the amount of fiat news they are consuming, but also how that compares with all available content, the content consumption patterns of others and, most importantly, their own content consumption habits over time. Some of that feedback, however, will be designed to highlight topics consumed by users at high rates - when you're overswirling - and to highlight topics and events to which users may already have gone noseblind.

Making up our own minds sometimes means finding ways to fight that mind's tendency to tune out and forget. We think what we're working on will be one tool.

But it can't be the only one. And it won't. To that end, this will be a major topic at our upcoming Epsilon Connect event. We want your input and feedback on this development process. If you want to give that input and feedback, this event will NOT be your last bite at the apple. But it will be the first big one - and one that comes with the opportunity to help us design this the right way from the very start. We hope you can join us in Nashville.

Even if you can't, even if you think we're approaching this in a dumb way or just the wrong way, we encourage you to start thinking about these problems all the same. For you and the fellow citizens whose vision for your community you want to realize, how will you remember? How will you protect yourself from going noseblind to the things that really matter?

Comments

Speaking from personal experience only, there are some topics which I never go noseblind to. Even if there is a lack of coverage for a period of time on a particular pet topic, my sniffer is always on the lookout for it. I’ll bet others do this too.

But how many topics fit that description, and how deep is my bias for having those specific topics lodged in the brain? A couple dozen out of potentially hundreds or even thousands? I can do better, but how? Maybe the beginning of an answer is developing here.

The y-axis of your graphs show “% of topics at peak news flow share”, all starting at 100%. Might there be utility in having a quantitative element with number of news articles here to illustrate breadth of coverage per topic? It would be interesting to see if the ones which spike the highest initially correlate to those with a longer lifespan.

It would be useful to have a list of topics which the “politically diverse ET team” views as important long term. The Pack can suggest inputs here too, in case something is missed, and perhaps even vote on it for inclusion to a list. What would the ideal number be? If we vote one in, do we have to vote one out?

Coffee cup #1 went dry 15 minutes ago. Gonna see if #2 has had enough time to reset olfactory habituation

There is utility in that to answer some questions, I think, but differences in scale between those stories mean you inevitably end up with a few dozen charts to present the data in a way that conveys that utility. It also makes any underlying tendencies or biases in our dataset - which is very large but not complete - somewhat exaggerated to view it in that way. Coverage share by a fixed group of large-scale topics IS something we intend to make a standard part of the Fiat News subsite, but even then our predisposition is probably to present it as a percentage of newsflow (although that does capture the volume more directly).

The Fiat News subsite will have aggregates of topics at different levels. The top level will present both coverage density and fiat news density over time for things at the “US Politics”, “US Markets” or “US Economy” scale. The next level down will break those aggregates into smaller chunks. Right now we have a list of five top level aggregates and twenty-five second level aggregates we plan to track. From there, the question will or could be how we want to track things that are less “topics” than they are explicit stories, and for how long. I think that’s where we’d benefit from feedback from the Pack. Much like you observe about yourself, we are humans that have our own sets of things we keep an eye on. Wherever we can be systematic about incorporating new ideas at that third level, all the better.

In the absence of a systematic mechanic we all feel comfortable with, I’m very open to the third level being user-driven, or at the very least heavily user-influenced.

Am I wrong in thinking Nixon does not get impeached in this current environment?

Not wrong. It was other Republican’s that broke the dam. Not today.

I was curious about that and know you’ve mentioned it before in notes. Is the corpus all financial press, public and private, in the US or is it more expansive than that?

I think this is really a must for the ethics of ET in a purpose aligned operation!

I’d also like to nominate one extremely newsworthy story for a test of its half life as well as like a heat map of its geographic penetration: the BLM protests and how they were used as an “accelerant” by the likes of the Boogaloo Boys and other anti-government militia groups to take advantage of political unrest to try and seed a civil war in the US. Call me a socialist, if that’s all you’ve got, but I think it’s an extremely newsworthy story with giant legs.

Boogaloos like Air Force lieutenant Steven Carrillo used cover of POLITICAL PROTESTS to INCITE RIOTS (and in Steven’s case MURDER POLICE), and this happened in different areas of the country including the Bay Area, Las Vegas, and others I’m now forgetting. That was before Trump gave the command to Proud Boys to “stand back and stand by” and before these types joined their Christofascist comrades and an assortment of highly suggestible, low information Trump voters radicalized largely on the internet during a pandemic to storm the US Capitol after being called to spiritual arms by the NAR’s shofars and a very belligerent vitamin pusher that I still maintain needs a really good, hard kick in the nuts and some time in a maximum security prison filled with cellmates that know people killed in school shootings. Sorry for the run on but had to get it all out!

This story really stays with me for reasons hitting at all circles of salience for me: the enemy within our military, the Sagebrush Rebellion and its heirs and related echoes of the Crusades, the murder of a sheriff and a federal security officer by a boogaloo when I’d seen an old friend in Idaho get sucked into that on Facebook in this same time frame, some of the people I grew up with in Wyoming getting similarly radicalized on Facebook as seen in their shared death cult images of a stylized Punisher as they railed against “rioters”, the constant (and persistent) willful conflation of legitimate protest and rioting, and last but not least the incredible story of heroism from the citizen in Ben Lomond who tackled the murderous traitor Carrillo before the police could find him and arrest him. This was after Carrillo had ambushed a county sheriff and attempted to hijack an escape vehicle, and after he’d written with his blood on the hood of another car these phrases: “boog”, “I became unreasonable”, and “stop the duopoly”. The story is just incredible from a storytelling perspective and it has all kinds of ongoing relevance for politics, tech, and society.

Yet I believe there is some fundamental relationship between proximity and salience of information contained in narratives/stories. That proximity might be mostly geographical but it could also be thought of in terms of communities we participate in. I think this story has stuck with me because it was a local one during the most heated days of the pandemic and because I care a lot about these militia types and have a frame of reference for that having grown up in Wyoming.

Not all, and not US-only. It is a really expansive dataset of English-language sources from both the US and abroad that we scrape (to a lesser extent) or buy directly (to a much greater extent) from Factiva and Lexis Nexis, two of the primary commercial vendors of this kind of data. We have two vendors because it was important to us to ensure we had 99%+ coverage of the largest 50-100 sources in each of news website, newspaper and blogs, plus the major newswires and large regional representation (usually the largest papers and sites in English in large foreign countries). There are holes in each of their coverage rosters.

I absolutely hear you on this.

I’d also like to push back a little bit, not because I don’t think we might discover exactly what you’re talking about, and not because I don’t think what you’re saying would matter if we did discover it, but because I think that an analysis that started with this prior would absolutely reflect this prior.

Wouldn’t the right way to approach this simply be to start from the analysis of BLM Protests as a news story in comparison to other comparable news stories, to explore how affected language was used in that coverage, then dive into clusters of sub-topics and framing to see whether language indicative of what you describe was present and influential?

That is, I personally don’t think the characterization of third-level news stories we track should answer the question they should be asking, But it’s possible I’m missing something in the idea or the potential in this approach. Happy to hear it, if so!

For a variety of reasons including the length of news cycles today, no, I don’t think you are wrong.

Then the water which is the “news cycle” has changed and it is in my own self-interest to learn how to swim in this new water.

Then the water which is the “education system” has changed and it is in my own self-interest to learn how to swim in this new water.

The running theme across ET notes for me personally is that I can’t change the water. I can however work on myself to better recognize the changes in the water and make different choices based on the new water.

I won’t say that you shouldn’t believe that. I will say that it is not exactly what I believe, anyway, or what I’m at least trying (and often failing, probably!) to convey.

I don’t think the water can be changed by relying solely on the tools that create and maintain it. I think we can take actions as you describe that, in concert with others of like mind, can have the effect of creating new pools in which to swim. And maybe, just maybe, those can become the new water. As below, so above.

I hear you that I used biased language. That was on purpose as I’m self aware enough to realize this is also a platform here on ET!

And I appreciate the push back. How might we find the salient characteristics of this story as it relates to our experiences of the world? My experience of it here in SF is obvs different than yours. That’s why I sort of added my qualifier at the end that this one really sticks with me, i.e. I haven’t become noseblind, but that may be because of where I live and my network and personal interests. Hence my wanting some sort of heat map to see where these stories live, which is different/additional to the approach you outline. And as I type this out I think it could also be interesting to add additional data to the corpus.

I am reminded of an event I went to here in SF that was a talk by someone from the Internet Archive. They were announcing how they were now going to be adding radio to their archives and mentioned how that is actually the media channel through which a lot of Americans receive their political information. If you think about the rise of shock jock types over the last few decades this is obvious. If you’d heard that talk or watched the documentary The Brainwashing of My Dad or if you are a truck driver or construction worker that needs to fill up lots of quiet hours working with your hands you’d maybe have a greater awareness for that. I don’t mean you, Rusty, just the impersonal you btw.

Continue the discussion at the Epsilon Theory Forum...