September 17, 2025·Sports

Luv Ya Blue

Jeremy Radcliffe·article

Week 1 of the 2025 NFL season featured a number of exciting games, but the game that football junkies were most anticipating delivered far beyond our highest hopes, as Josh Allen led the Buffalo Bills to an all-time comeback win over the Baltimore Ravens. Trailing by 15 points with under 5 minutes to play, Allen shifted into Quarterback God Mode and the Bills won it on a last play field goal that gave the Bills a 41-40 win. The comeback was thrilling, and historic - it was the first time ever that an NFL team had won a game when facing a 15-point deficit in the final 4 minutes (prior to the game, teams in that situation had 0 wins in 717 such situations).

But it wasn't even the biggest comeback in that stadium's history, as we Houston Oilers fans know all too well. They call it Highmark Stadium now, but it's still Rich Stadium to me, and probably to a lot of Buffalo fans. That house of horrors is where my team suffered a mortal wound, blowing what is still an NFL record 35-point second half lead in a wild-card playoff game in January of 1993, losing on . . . a last play field goal that gave the Bills 41 points.

These days, the Oilers only exist in highlights, on merchandise and in our hearts, but even before last week's bitter reminder, they've been on my mind even more than usual. This summer, fans of the Oklahoma City Thunder celebrated their game 7 NBA Finals victory – the city’s first professional sports championship – while Indiana Pacers fans mourned. Their dream season ended in a nightmare in which they lost not just the NBA championship, but their breakout star Tyrese Halliburton, who will miss next season after he blew out his Achilles trying to will his team to a title.

They weren’t the only losers.

As devastated as Pacers fans were, I couldn’t help thinking of another group of mostly forgotten fans who had to be feeling, well, triggered. It’s been almost twenty years since owner Clay Bennett moved his franchise from the gray rain of Seattle to the red clay of Oklahoma. I’m sure there were some Sonics fans who were torn watching Kevin Durant, who played a year for the Sonics, and Russell Westbrook, who was drafted by the Sonics days before the move was finalized, team up with James Harden to make a run at the championship in 2012. But the Thunder lost to the Heat in the Finals and then had to retool after trading Harden to the Rockets. Those Sonics fans who did not “travel” to OKC with the team undoubtedly felt some level of schadenfreude as the team struggled to reach its previous heights. Even all these years later, I can guarantee that a sizeable portion of those suffering Sonics fans were hurting all over again watching the Thunder celebrate (although perhaps taking some solace in the fact that the team and their fans really didn’t seem to have any idea how to party).

I know exactly how they felt, because, as a lifelong (and long-suffering) Houston Oilers fan, I had already lived it.

In January of 2000 I watched the Tennessee Titans come within a yard of winning a Super Bowl in the first season at their new Nashville Stadium. Certainly, there was a part of me that was rooting for guys like Bruce Matthews, Steve McNair, Eddie George and Frank Wycheck, but mostly, I was relieved. It was unfair enough that those Nashville newcomer fans even made it to the Super Bowl – the closest the Oilers came was in 1980 when they were robbed of a potential victory over the powerhouse Steelers by a blown call on a clear touchdown catch by Mike Renfro – but for my team to win a Super Bowl for their city, especially so quickly, would have been like rubbing salt into the proverbial wound.

That was a fresh wound in early 2000, about 3 years after the Oilers’ last game, a 21-13 loss to the Cincinnati Bengals at the Astrodome on December 15, 1996. I attended that game, as I had about a hundred Oilers games over the previous 15 or so years. Eddie George did something that I and plenty of other Oilers diehards will never forget – he ran all the way around the field high-fiving those of us that had moved down to lower-level front row seats at the end of the game for one last goodbye. I had cried leaving the Dome after tough losses before – like when Joe Montana broke our hearts in the AFC Divisional Playoff in January 1994, the last one at the Astrodome. Or when the Steelers’ Rod Woodson forced an overtime fumble in the Wild Card game that got Jerry Glanville fired back in 1989. This time my tears were saltier and the pain was different. It was less like a loss and more like, well, death. Even almost (unbelievably) thirty years later, my wound has scabbed and scarred, but it hasn’t fully healed.

I read something last year that really blew me away.

It’s a book by a psychologist named Terry Real called I Don’t Want to Talk About It. It was, coincidentally, published a month after that last Oilers’ loss. It was a groundbreaking work about male depression, and Terry set the stage early in the book when he stated that by the age of three, boys have learned that it’s not safe, much less cool, to share their feelings. Well, you can probably imagine how that turns out for most of us – I turned fifty last year and am finally getting a handle on how to feel my feelings, much less express them. But sports have always been that place where it hasn’t just been OK for boys and men to share their feelings – it’s been encouraged. No wonder so many of us love to not only play sports, but to watch sports. It’s a license to let it all out, where going batshit crazy together after a big play can instantly turn the unknown fan in the next seat or barstool into your best friend.

To the true fan – the fanatic – it is even worse. When a team leaves a city, the true fan feels like he lost something big, something he loved. And yes, love is the right word for how a true fan relates to their team. When the team leaves, the true fan goes through the five stages of grief, from denial to bargaining to anger to depression and then (grudging) acceptance. They are tormented by all the memories, including the good and the bad. And the memories are vivid. Although memory is a curious and ephemeral thing, the relationship between emotional intensity and the clarity and persistence of memory is one of the most well-established findings in cognitive neuroscience. Amygdala-hippocampal networks include specialized emotional memory circuits that encode memories with greater persistence and intensity on an almost linear basis to emotional arousal. Those memories come along with a lot of triggers. I still have to turn the TV off when those damn Buffalo lowlights come on, like they did after Sunday night's game.

I was raised this way. My maternal grandmother was very reserved and didn’t know what to make of this sports-mad house when she came to visit us. Until the Alzheimer’s kicked in, she used to tell the story of one of the first times she came down to Houston to visit us, when my brother (still in diapers) and I allegedly greeted her at the door shouting the Oilers fight song at the top of our lungs: “LOOK OUT FOOTBALL! HERE WE COME! HOUSTON OILERS! NUMBER ONE!” Mamo’s story checks out – that would have been around 1980, which was pretty much the peak of the franchise, the heart of one of the greatest organic team and city lovefests in sports history, the Luv Ya Blue era of Bum Phillips, Earl Campbell, baby (Columbia!) blue jerseys and the Derrick Dolls.

The Luv Ya Blue thing was crazy – after both of the AFC Championship losses to the Steelers, tens of thousands of fans showed up spontaneously, lining the streets from the airport to the Astrodome to welcome their beloved Oilers home. Over 70,000 fans jammed into the Dome for a pep rally after the 1980 loss. But after failing to tear down the Steel Curtain in those back-to-back AFC Championship games, the bloom was off the Tyler Rose, and Earl left, along with Bum, for New Orleans. Houston fans, in exchange, took up the habit of wearing papers bags over their heads at games, which had first been popularized by suffering Saints fans in 1980. It was bad – the Oilers lost 8 out of 9 games in the strike-shortened 1982 season and then posted back-to-back 2-14 seasons in 1983 and 1984. My family stuck with the team, and we still made it to almost every game. Our seats were in the upper deck of the Astrodome – the 400-level seats, with stairs so steep it’s a miracle we never saw worse than a few spilt beers.

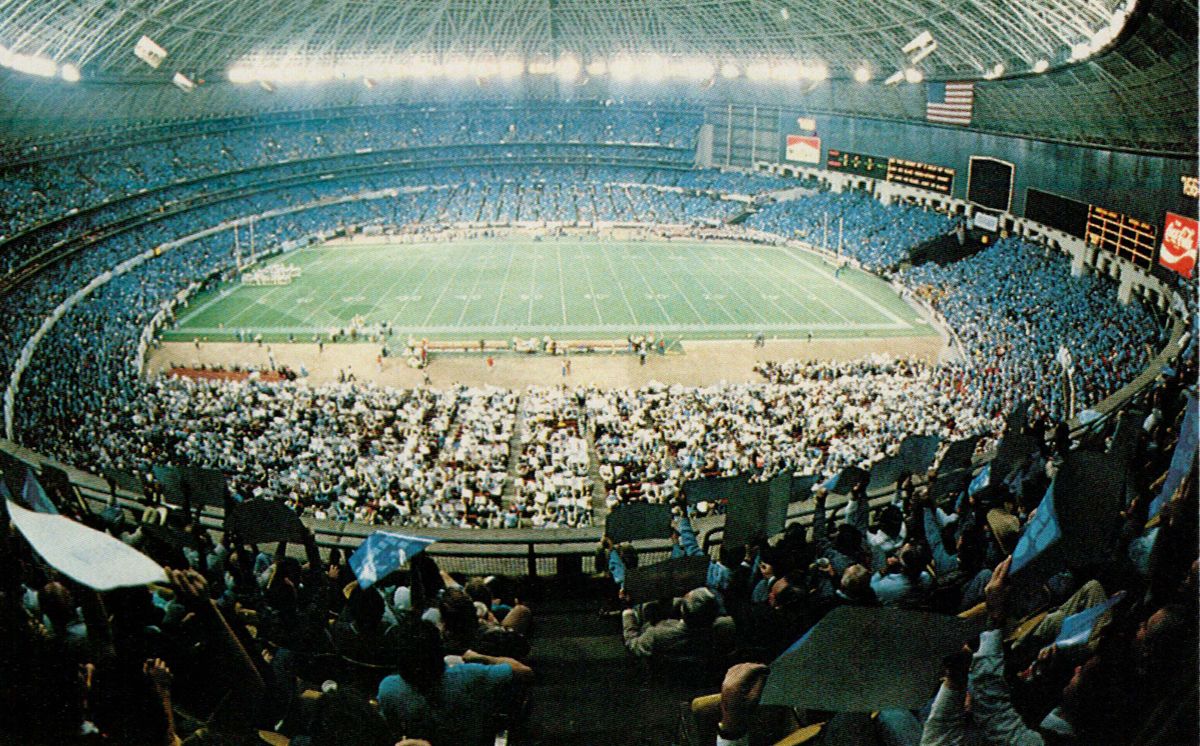

An Oilers game at the Astrodome during the Luv Ya Blue era (thanks to "Armadillo Jim" Schmidt armadillojim.com)

Finally, when I was about twelve, the smart moves by the team’s maligned GM Ladd Herzeg started paying off. He used high picks on Hall of Fame offensive linemen like Mike Munchak and Bruce Mathews and brought in another Hall of Famer, Warren Moon, from the Canadian Football League to be our quarterback. And now it wasn’t just my family in those seats – my friend Andrew eventually got his own single ticket right next to ours and came to every game with us. I loved watching Warren throw the ball from those upper level seats. You could see the whole field and how the plays developed. When one of our wide receivers was breaking into open space, we’d start getting excited, because the odds were pretty good that #1 was going to see him and then hit him with a frozen rope. Sometimes I watched offensive plays with my binoculars so I could see the tight spirals he threw, following the ball in the air with the anticipation of not knowing whether it was on target until, most often, it hit the intended receiver right in his hands.

We didn’t just go to Oilers game at the Astrodome. My family would paint our faces, make signs and go to away games, including two of the most heart-breaking losses in franchise history: RFK Stadium in November 1991, when Ian Howfield missed a chip shot to win the game and it felt like every fan in the stadium turned to yell at and taunt the Radcliffes; and Mile High Stadium in January 1992 when John Elway and the Broncos came back from a 21-6 deficit to send the Oilers home in the Divisional round. But I suppose I am grateful that we didn’t travel to Buffalo the following year, because it turned out that the Denver loss was just a warmup for, with apologies to the 28-3 Atlanta Falcons, the biggest choke in sports history. That 41-38 OT loss to Jim Kelly and Thurman Thomas – excuse me, Frank Reich and Kenneth Davis – the greatest gut punch loss ever, sent me into a month-long depression at college during which I slept until noon and attempted to drown my sorrows with WaWa chili cheese dogs; my brother back home took out his frustrations more simply by punching a hole in the living room wall (my stepdad put an empty picture frame up around it, which stayed until my family moved a few years later). But that brutal loss was the beginning of the end for the franchise in Houston. The Warren Moon-led team had one last gasp in them the next year after they brought in Buddy Ryan as the DC, only to lose a playoff home game to a washed-up Joe Montana wearing Chiefs gear. When the team hit the skids the next couple of years the fans, and the city’s mayor Bob Lanier, just weren’t in the mood to support building a new football stadium for the unlikeable owner Bud Adams, who’d cried wolf about moving to Jacksonville for years. Seemingly overnight, the Oilers were facing their last season in Houston.

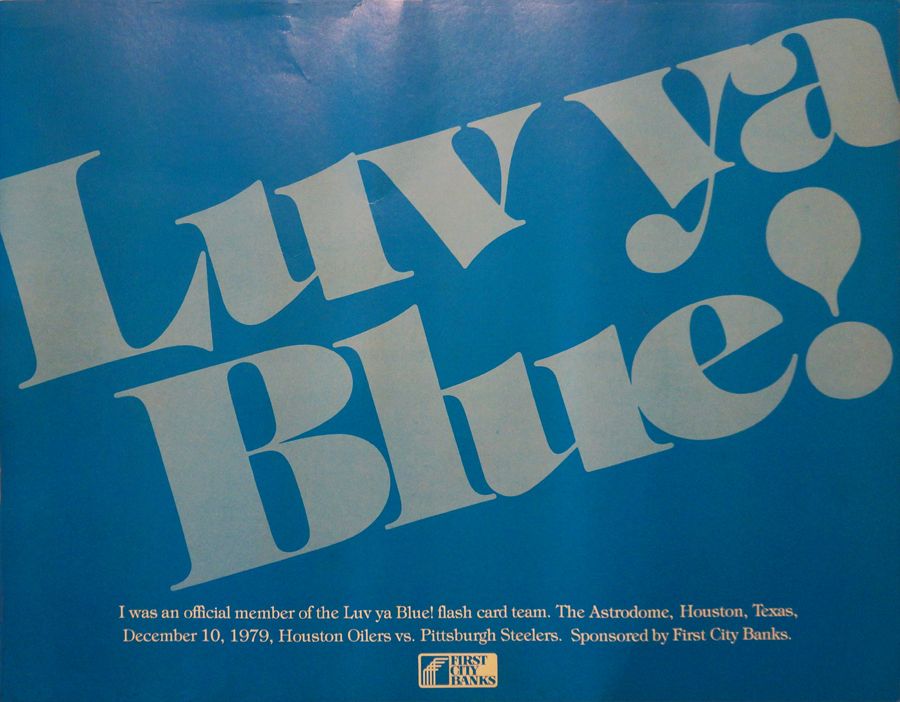

The original Luv Ya Blue flash card that sparked a love affair between team and city (armadillojim.com)

Today, the Oilers live on in Houston’s collective memory, their Luv Ya Blue era immortalized in retro shirts and wistful conversations. The Astrodome, too, endures – not as a vibrant stadium, but as a ghostly landmark.

The Dome sits there still on the former “Astrodomain” complex site, just a couple of Warren Moon bombs away from Reliant Stadium, the home of the replacement franchise that Houston landed just six years after the Oilers left. Only twenty years after it opened as the eighth wonder of the world in 1965, the Dome had fallen behind newer stadiums in terms of capacity and amenities, and Bud Adams wasn’t happy about it. He complained and threatened to move the team to Jacksonville. In 1987, Harris County responded with a $67 million renovation that added seats and luxury boxes at the cost of some of the scoreboard real estate, but these changes weren’t enough to satisfy Bud. He continued to complain and threaten to take his team elsewhere. It was a swift on-field collapse when the Oilers posted a miserable 2-14 record in 1994, but the relationship between owner, media and local politicians had been deteriorating for years. By the time the team canceled a 1996 preseason game against the Chargers because of allegedly unsafe field (AstroTurf!) conditions, it was all over but the crying.

The biggest beneficiary of this disaster was Astros owner Drayton McLane. Backlash against local politicians was significant, so the conditions were right for Drayton to get a new ballpark. Enron Field opened in the spring of 2000. I’ve got the commemorative game ball from that first game. Of course, I was also in attendance for the Astros’ last regular season home game in October 1999, and also for their playoff loss (to the Braves, again) later in October. The Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo continued to use the Dome until 2002, when George Strait closed out the Dome for good at the final Rodeo concert of the year. Twenty-three years later, you can’t really say the Dome still stands. No, it just sits there, a rotting, asbestos-ridden reminder of times long past, home not to the Oilers or Astros, but to a large population of rats and cats.

But I relive the good old days through my collection of Astrodome memorabilia. I own four pairs of original Dome seats, in red, yellow, orange and blue (not a complete set because I don’t have the silver Loge level seats) that I picked up at the official Astrodome “yard sale” in 2013. Organizers of that event underestimated how many of us Dome-heads wanted a piece of history. Even though you had to buy tickets to get into the event, the lines to get into the Reliant Center forced me to wait in the concrete-intensified Houston heat-midity for about two hours before getting in, by which time most of the cool stuff – signs and field crew jackets and the best of the concession stand equipment – was gone.

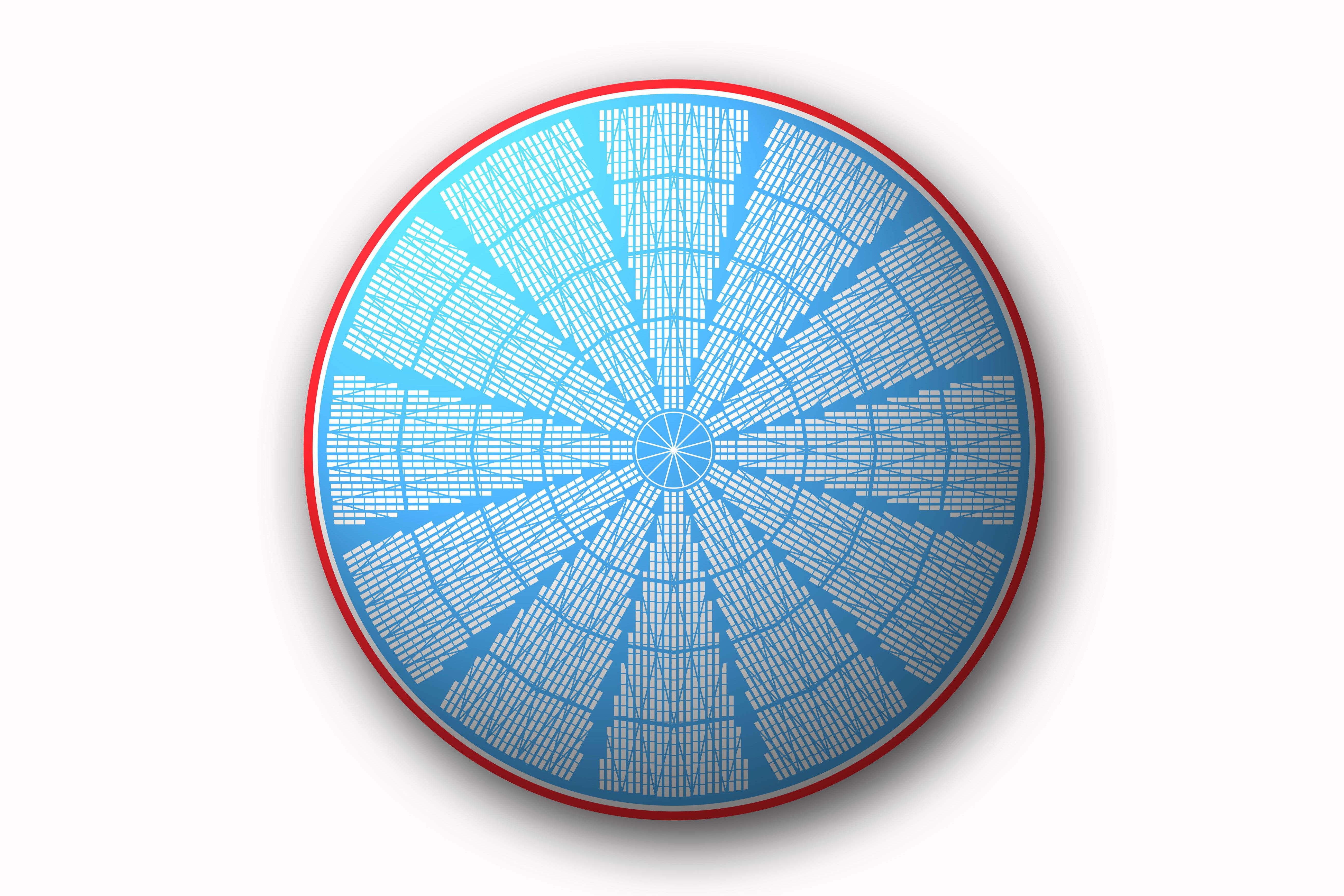

Some of my other favorite Astrodome stuff isn’t vintage – they are metal signs made by my friend James Glassman, the self-proclaimed Houstorian. One is a 3 foot-diameter circle with the pattern from the Dome’s ceiling girders and the other is a big traffic sign that has one arrow pointing straight with “DOME” over it and a right turn arrow with “WORLD” over it. It’s not just the Dome that us Houston Gen-Xers miss – we had a whole amusement park right across the 610 Loop. We used to get season passes and get dropped off all the time during the summer break, riding Greased Lightnin’ and the Texas Cyclone over and over. My first “date” in fifth grade was to Astroworld. They tore it down twenty years ago and had big plans for a multi-use development, but then the financial crisis hit and so it’s still just a giant empty lot. I now grieve that loss by torturing my kids with AstroWorld stories, tales of fun and independence that they never got to experience.

Astrodome art from James Glassman (houstorian.org)

Astro Dome / World art from James Glassman (houstorian.org)

These are good memories! But they’re tinged with sadness, with that sense of, well, death. It’s like what I imagine it’s like for divorced couples. Divorce colors everything that went before it. Even the brightest moments are dulled. Changed. My parents got divorced in the mid-80s but other than that pain, losing the Oilers was the worst thing I experienced before Real Life started happening. No matter how bad the last loss of the season was – and we lived through a run of epically brutal ones – we could always fall back on that old sports fan chestnut and dream about “getting ’em next year.” Not this time, and not ever again for us Oilers fans. I think that’s what a lot of the Oilers and Astrodome memorabilia I’ve collected is about, the sports equivalent of the locket with a piece of your deceased parent’s or spouse’s hair in it, something to hold on to after someone you love has died. In some ways it’s almost harder to deal with – we all know that the people we love will eventually die, and that we will, too; but our teams are supposed to live on, if not forever, indefinitely.

Winners and losers? Bud Adams won the battle but in many ways lost the war, dying a hated man in his hometown of Houston, where he still lived even after moving the team out of town. Some lauded Bob Lanier for taking a principled stand against wealthy team owners, but it was really about Bob’s ego and his denial of the economic reality of being a big city with citizens who want major sports franchises. Within a decade the city and county had doled out billions to keep the Astros and Rockets (whose owners soon thereafter cashed out for a total of about $3 billion) and to bring back the NFL with the Texans. Houstonians demanded a replacement NFL team, and to get one, the next group of politicians had to cut a terrible stadium deal. Under that agreement, the Texans pay almost zero net rent to use the stadium and aren’t required to help pay for maintenance or repairs, much less renovations. And wouldn’t you know it, it’s deja vu all over again. Earlier this year, the Texans announced that they would be seeking a new stadium, in large part because the County is behind on hundreds of millions of dollars of repairs. The Astrodome might not be the only physical reminder of the costs of bad governance down on Kirby Drive.

But I’m not alone as an Oilers fan in 2025. Sure, some just love them for the colors, uniforms and logo – just check out Super 70s Sports Guy on Twitter, or the Titans website. Luv Ya Blue lives. The Oilers may have been losers, but even in losing, they were spectacular, losing in ways that no team had before or has since. And they were colorful on and off the field, from QB Dan Pastorini dating Farrah Fawcett and punching Houston Chronicle columnist Dale Robertson to Ladd Herzeg’s bar fight to Jerry Glanville’s feud with Bengals coach Sam Wyche to DC Buddy Ryan literally punching OC Kevin Gilbride on the sideline during a game. And the name was so unapologetically Houston, celebrating the city’s main industry, that others even then loved to bad-mouth, with those oil derricks on their helmets. It’s really no wonder that such a strong bond formed between city and team that the relationship itself became a thing, with a name, that has outlasted the team now by almost three decades.

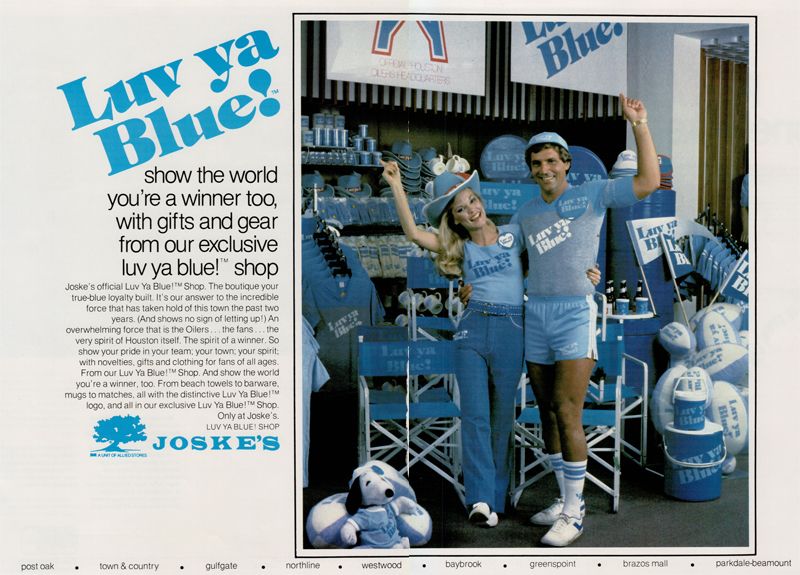

Joske's department stores (sold to Dillard's in 1987) in Houston carried an extensive array of Luv Ya Blue gear (armadillojim.com)

At least Seattle learned from some of the mistakes made by Houston (and the Hartford Whalers before them) and negotiated a friendly release of the team. In doing so, they were able to keep the rights to the team’s name, colors, jerseys and logos. The Sonics are like Han Solo in Empire Strikes Back, frozen in carbonite, but ready to return. The Oilers and their colors and records are in a zombie purgatory of sorts, let out every so often for a throwback game.

Houston’s professional football situation is unique. Baltimore lost the Colts but the Ravens had so much early success that a lot of their pain has been washed away by the joy of victory and now by the sustained excellence. The Browns got the Browns back. The Rams and Chargers don’t really count because hardly anyone in LA cares about football, which is why Houston got the Texans so quickly when LA still didn’t have a team at all. St. Louis, Oakland and San Diego are currently without teams. In the NBA, Seattle is joined by Vancouver, Kansas City and again St. Louis and San Diego as former league cities. Charlotte got the Hornets back. Only New Orleans (lost the Jazz in 1979) have been replaced by a franchise without retaining their old name and colors. And the Jazz spent just five years in New Orleans and never made the playoffs.

You could accurately call the Oilers many unflattering things, but you could never call them boring. Like, the Houston . . . Texans. Right from the choice of the name and the colors (“Battle” Red, “Deep Steel” Blue, and “Liberty” White), it was clear that these were no Oilers. Yes, I bought PSLs and I still root for the Texans, but it isn’t the same, and the loss of the Oilers still hurts. Ironically, it’s taken a dispute between feisty Texans owner Hannah McNair and Titans owner Amy Adams Strunk, Bum’s daughter, over the Titans’ petty attempts to own not only the Oilers name and logo but their baby / Columbia blue color, to get me fired up about the new(ish) team here in Houston.

Big deal, the non-fanatic thinks. You were only without a team for six years, and yeah maybe the new jerseys aren’t as good, and the new team hasn’t won the Super Bowl, but they’ve been generally competitive and won a bunch of division titles. About the same as the old Oilers in Tennessee. Well, it is a big deal. Because as a fanatic, you don’t just watch your team. You live your team. Their story is part of your story. I’m blessed to still be close and close to my family, so we get plenty of time to reminisce and share family lore with the next generation, and we still talk about those laser beams of Warren Moon, the face painting, and the painful losses. Denver. Washington. Even Buff – actually, we still don’t talk about that one. It’ll always be too soon. And maybe that’s the point – some wounds don’t heal, they just become part of who you are. The Oilers didn’t just leave Houston; they left us. But in some strange way, thirty years later, we’re still here. Luv Ya Blue.